These Fighting ‘Mighty Midgets’ Packed Big Guns

The Asiatic-Pacific Theater in World War II culminated with a grueling, bloody amphibious campaign to capture one Japanese-held seabound stronghold after another. To deliver soldiers to the various beachheads along the sea route to Japan, the U.S. Navy relied largely on LCVPs—landing craft vehicle personnel, or Higgins boats—each capable of transporting up to three dozen GIs. Little more than 36-foot bargelike shells made largely of plywood, LCVPs left their human cargoes vulnerable to intensive enemy fire both en route to and on lowering their ramps onto the beaches.

The Higgins boats did, however, have guardian angels—powerful amphibious support ships popularly known as the “Mighty Midgets.”

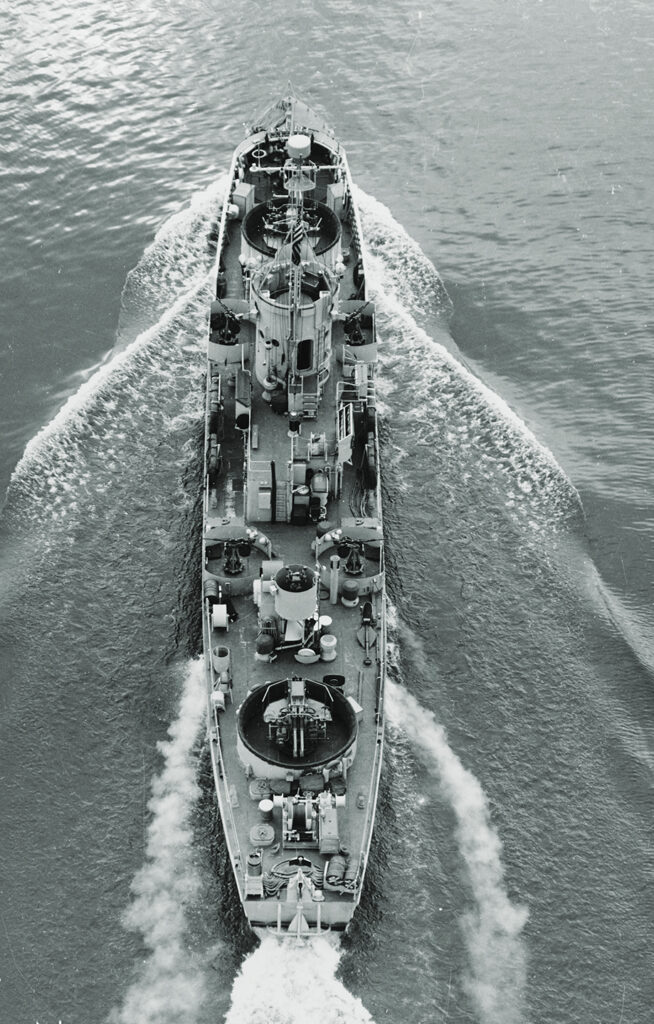

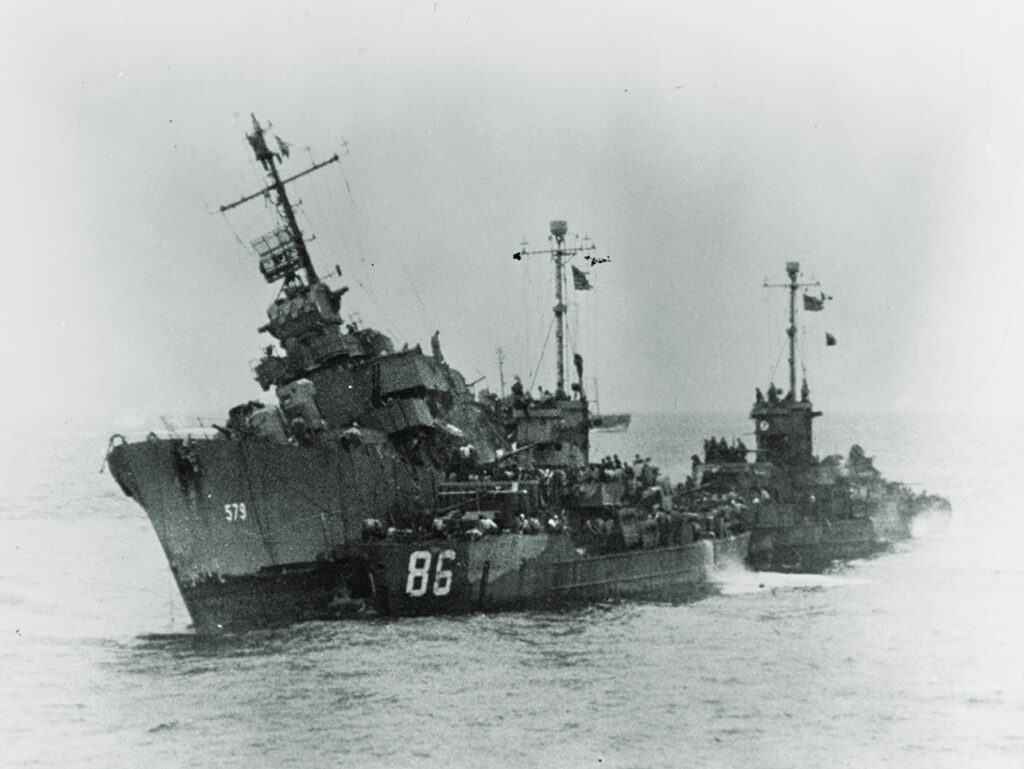

In 1943, recognizing the need for a large, close-in fire support vessel that was not simply a modified troop carrier, the Navy contracted the George Lawley & Son Shipyard of Neponset, Mass., to design the first of its kind. Between May 1944 and March 1945 Lawley & Son and both the Commercial Iron Works and the Albina Engine & Machine Works of Portland, Ore., built 130 such vessels for service in the Pacific. Each ship was given a number rather than a name. Their official designation was Landing Craft Support (Large) (Mark 3)—commonly shortened to LCS(L) or simply LCS—but on proving themselves in action the vessels became known collectively throughout the Navy as the “Mighty Midgets.” With its 158-foot-6-inch length, 23-foot-3-inch beam and a flat bottom that allowed for a shallow draft of less than 6 feet, the LCS was ideally designed for inshore fire support. By contrast, destroyers of the era, at more than twice the length with a 9- to 19-foot draft, were unable to achieve the proximity required for the sort of close-in precision fire capable from an LCS.

the background, the LCS gunboats are in the wake of the landing craft, firing on the beaches.

(Bettmann (Getty Images))

With a maximum speed of scarcely 16 knots, the LCS was not fast (one chronicler describes it as “sluggish”), but it was both powerful and versatile. Designed for the dual purpose of supporting amphibious landings and intercepting interisland barge traffic, the Mighty Midget was not built for looks. “The ship in itself is nothing,” recalled Lt. j.g. Powell Pierpoint, the executive officer of LCS-61. “She is unlovely to look upon and has neither grace nor speed. She has not even the dignity of a name.” In his next breath Pierpoint sang her praises. “Her history comes from the men who are in her and the job they did with her.…Theirs was to be a fighting ship, with guns and rockets. No bow doors, no ramps, no cargo holds; just guns and rockets, a small galley and 71 men and officers. Lofty beside the squat LCIs and lopsided LSMs, she simply bristled with guns.”

In fact, the LCS was the consummate gunboat, carrying more firepower per ton than even the Navy’s largest battleships. Recalled Lieutenant John Harper, the skipper of LCS-52, “Like her sisters, she was, pound for pound, arguably the most heavily armed gunship on the water.” At the bow was mounted, depending on the vessel, either a Mark 22 3-inch/50-caliber gun or a single or twin Bofors 40 mm L/60 antiaircraft gun. Another twin Bofors was mounted forward in the number two position. Amidships on the superstructure deck were two Oerlikon L70 20 mm rapid-firing antiaircraft guns with gyro sights, one to port and the other to starboard. Aft on the main deck, port and starboard, were two more 20 mm guns. Each of the four was capable of firing 450 rounds per minute. Astern was another twin Bofors, each barrel able to fire up to 140 rounds per minute. Available when necessary were four removable .50-caliber machine guns, which could be mounted two to a side. Steel splinter shields ringed the gun mounts, pilothouse and conning tower.

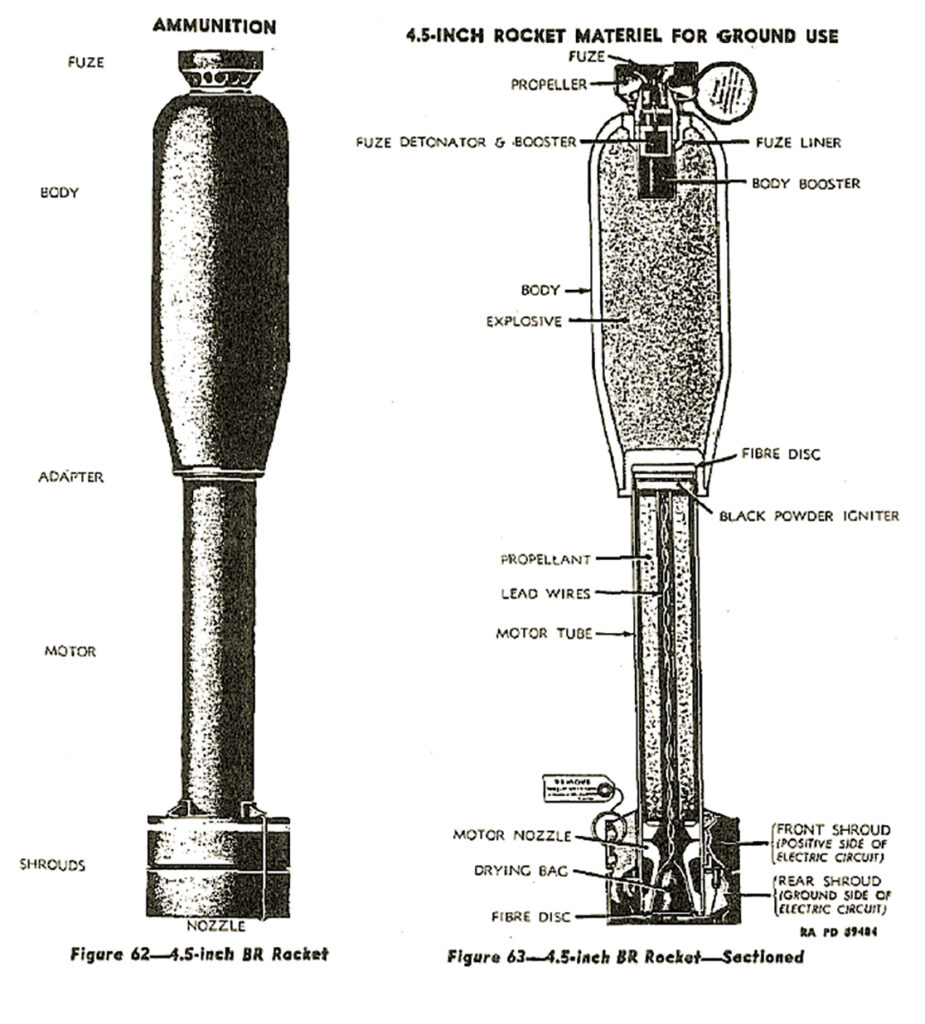

Finally, athwartships between the forward twin Bofors and the bow gun were 10 Mark 7 rocket launchers, welded to the deck in two groups of five at a fixed 45-degree angle. All told they cradled 120 barrage rockets, a dozen per launcher. The launchers could be fired either individually, for ranging purposes, or in a single devastating salvo. Each 4.5-inch rocket delivered a payload equivalent to a 105 mm shell, or a 20-pound bomb. Understandably, after listing its firing capacity, a wartime Navy training film dubbed the LCS a “pint-sized floating gun platform.”

During an amphibious landing operation an LCS would generally precede the first assault wave, making three runs in line with its sister gunships to strategically unleash cannon fire and rocket barrages against the beach at various prescribed distances. After firing its third salvo, the LCS would turn broadside to the shore, in column formation with its sister ships, and open up with all available guns on such targets of opportunity as enemy troops, pillboxes and gun emplacements. On this third run it would accompany the landing craft, remaining inshore to provide fire support as troops hit the beach. One observer described the Mighty Midgets as “looking something like a Fourth of July fireworks when all weapons were blazing.” Seaman 2nd Class Virgil Thill of LCS-52 recalled the first of his ship’s three runs at the beach on Iwo Jima:

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

The day has dawned clear…and we can see the beach now, slowly getting nearer. The radar man calls the yards. The 40 mm’s open with a crashing slam at 3,200 yards, and we can crane our necks to see the tiny shells make their little puff of smoke on the beach. At 2,400 yards the 20 mm’s add their chatter. A long way to go before our rockets are set off and we can port the helm to get out of here. When are the Japs going to let us have it? There is comfort in the constant pounding of our guns. Closer and closer. Each 50 yards seems interminable. Finally the signal to clear the forward twin and the single 40. Still no sign of a Jap on the rocky island. Suddenly the slamming hiss of the rockets taking off. The few seconds stretch out. Hard left rudder, port back one third. On our starboard beam is Suribachi, towering over us like a skyscraper; and that damned volcano is a giant pillbox. Well, this is where we get it—but nothing happened. Back out to the line of departure for our second rocket run, loading rockets as we go.

Spotting enemy positions ashore was often difficult. As LCS-52 skipper Lieutenant Harper recalled, the Japanese generally held their return fire, at least initially. “LCSs had not been fired upon when they had approached the landing beaches either the first or second time,” he recalled of the Iwo Jima assault, “because the Japanese defensive strategy was to not give away their gun positions until the landing craft were well on toward the beach.” Sometimes, however, a gun crew got lucky. While approaching the Iwo Jima landing beaches Ensign Laurance McKenna, the gunnery officer of LCS-31, watched as an observation plane flew low near the beach. “I happened to be watching the particular batch of bush that suddenly moved aside, clearing an AA battery to take the plane under fire, knocking it down with a single burst. Within 30 seconds the camouflage was back in place. I had the spot marked, and we had it wiped out in 60 seconds.”

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

(U.S. Navy)

Covering an invasion was only one of the Mighty Midget’s roles. In the words of author Donald L. Ball, the LCSs were “combatant seagoing ships capable of serving on patrols of all kinds, of escorting and protecting larger and smaller vessels in coastal waters and on the open sea, of destroying enemy targets on the beaches themselves and by directing the heavy gunfire of larger ships, of serving with destroyers and other ships on radar picket patrol on the high seas, destroying scores of enemy kamikaze planes and suicide boats and swimmers.” They are also credited with having saved the lives of thousands of sailors, plucking them from the sea after their respective ships had been damaged or sunk.

There was a great deal more to an LCS’s superstructure than its impressive armament. On the stern anchor winch it carried a strong steel cable suitable for salvage or towing damaged vessels. Four stout pumps and a network of hoses, as well as a monitor and hose on the bow, were capable of delivering some 1,500 gallons of seawater per minute at 200 pounds per square inch, ideal for fighting fires at sea. An onboard smoke generator, particularly when employed in coordination with those aboard sister ships, could create a virtually impenetrable smokescreen to conceal landing craft on approach, convoy vessels from air and sea attack or demolition teams working on or near shore. Finally, the LCS was equipped to spot and destroy open-ocean mines.

The LCS fleet provided effective close-in support in the Philippines, Iwo Jima, Okinawa and Borneo campaigns. They also served as radar picket line ships. For LCS crews the latter was the most unnerving and perilous duty, as it left ships particularly vulnerable to Japanese kamikaze attacks. Such attacks came in various forms—manned torpedoes, suicide aircraft, boats and swimmers—and as the war drew to a close, they came with increasing frequency and ferocity. LCS-52 skipper Harper recalled in detail the first night attack on his ship by a suicide plane:

(U.S. Navy (Associated Press))

(Naval History Heritage Command)

(Corbis (Getty Images))

It was so dark we could see nothing at all to shoot at most of the time, though the DDs [destroyers] were firing almost constantly. Suddenly a plane came out of the north and leveled off on a run directly at us. The little light from the gun flashes glittered on his prop so that we see him pretty well. By turning the ship a little we kept him on our beam so we could fire all our guns at once. It was hard for the gunners to see him when they once started shooting, so the gunnery officer and I had to keep telling them where to look. We knew he was heading for us for sure, so we kept up a hail of fire for his reception. The plane finally nosed down right on the fantail of our ship, and it looked like curtains for us. The after gunners looked right into the whirling prop to let go a last burst at point-blank range. This burst of fire caught the bomb load that the suicide plane was carrying, and the resulting explosion was terrific. Needless to say, the plane, bombs, pilot and all were blown to bits right in our faces. Plane parts, engine fragments and shrapnel swept our ship from bow to stern. The quartermaster had stopped the engines without further orders from me, since I had been thrown to the deck by the blast. When I reached the fantail of the ship, I found the damage control party already at work. [Engineering officer Ensign Spencer] Burroughs had been killed instantly by shrapnel from the blast. A gunner forward was killed, and many men and Ensign [Adler] Strandquist, the first lieutenant, were seriously injured.

On another occasion LCS-83 barely escaped a night attack by a Japanese bomber. Despite bringing all its guns to bear, the crew failed to bring down the enemy plane, which flew so close to the deck that, according to the wide-eyed signalman, “It left tire marks on the radio antenna.” Suddenly, an explosion from below rocked the ship, as the enemy plane’s payload detonated underwater. Fortunately, it had exploded well beneath the surface, causing no damage to the vessel or crew. Notes author Ball, “It may have been the only instance when an LCS serving with the fleet on the high seas saw its flat bottom as an advantage.”

From the moment a Mighty Midget left port, life aboard could be trying. Prior to their initial embarkation most crewmen had spent little if any time on the ocean, and the LCS’s flat bottom certainly didn’t enhance their introduction. At the outset seasickness was rampant, as Larry “Pops” Cullen, storekeeper aboard LCS-52, described in an epic poem on the subject (see sidebar below).

(National Archives)

(Naval History and Heritage Command )

Even after the crew had adapted to the challenges of an ocean passage, other sources of discomfort awaited them. “The hardest part of all was not getting enough sleep,” Cullen recalled of the period his ship spent providing fire support at Iwo Jima. “We were on watch four hours on and four hours off, with general quarters for firing, aircraft watch and smoke duty thrown in. We got to where we paid no more attention to shell fire than we would a fly.…

We could even sleep while our own guns were firing, with thousands of Japs a few hundred yards away and Japs and American Marines fighting and dying.”

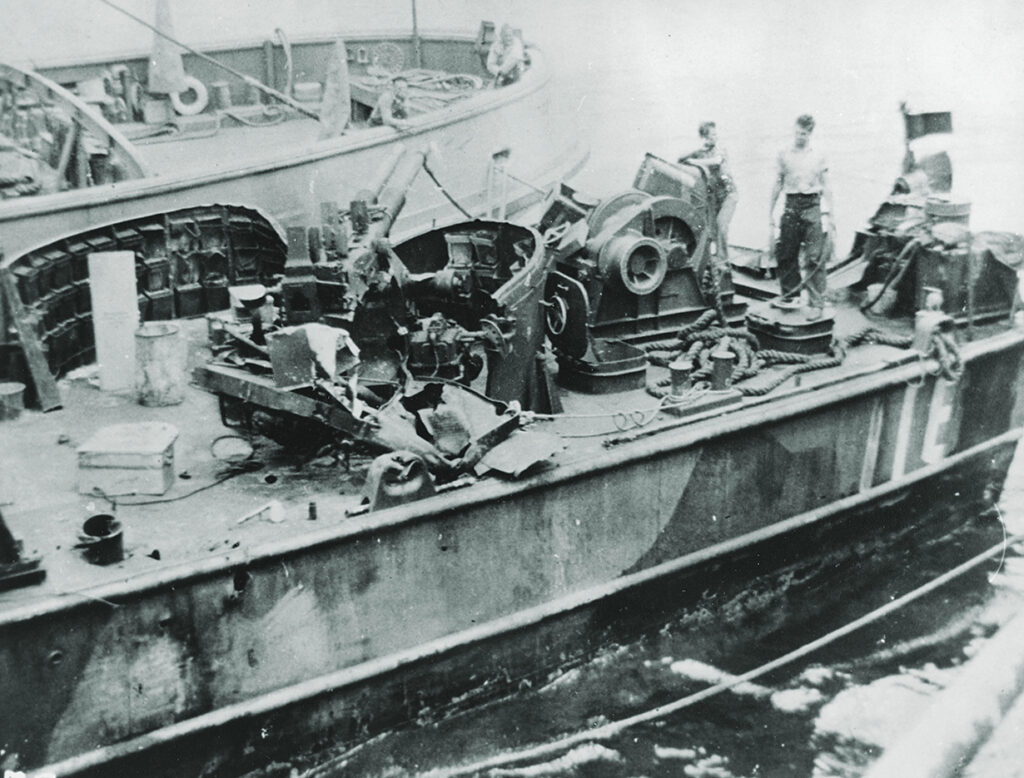

While under way other sources of danger lurked. Not surprising, the Mighty Midgets used up tremendous amounts of ammunition, and they often re-armed by tying up alongside considerably larger vessels while ordnance was transferred by hand—with great caution—from ship to ship. This outwardly simple procedure was made hazardous by rough seas, as one LCS-33 crewman experienced firsthand. “We were ordered alongside the battleship Texas to replenish our ammo supplies,” he recalled. “Texas was considerably higher and more ruggedly constructed than 33. Wind and waves combined to smash us unmercifully against the larger vessel, causing considerable damage to our superstructure.”

Sometimes ammunition was passed from one LCS to another, but the sea could prove every bit as unmerciful. On one such occasion LCS-35 was receiving munitions from sister ship LCS-56 but had to halt the procedure after having three of its docking hawsers broken, two gun tubs damaged, stanchions bent, recognition lights knocked out and 30 of its 101 frames (hull ribs) either broken or stressed. LCS-35 had to separate from 56 on a second occasion, again due to rough seas. The luckless vessel would be damaged twice more, once during a munitions transfer from the heavy cruiser Salt Lake City, the last time while taking on supplies from an amphibious assault ship.

(Naval History and Heritage Command )

The greatest threat to the LCS fleet, however, remained attackers from the skies and sea. Lieutenant Harper of LCS-52 recounted one close call while his ship was lying off Okinawa on April Fools’ Day 1945. “At dawn,” he recalled, “we were greeted by that popular Jap calling card, a suicide plane. The war was very close to us, we realized, when a neighboring ship caught the diving plane on her decks and went up in flames.”

During the course of the Pacific War five LCSs were sunk—three by suicide boats off the Philippines, and two by suicide planes off Okinawa. Of the 24 that took either major or minor damage, suicide planes and boats were responsible for 14. In contrast, enemy shore batteries accounted for only minor damage to three vessels. In all, 164 crewmen were killed, another 267 wounded. In recognition of their service between April and June 1945 eight LCS crews received the Navy Unit Commendation, while three were awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for their service at Okinawa and Iwo Jima. Lieutenant Richard M. McCool, skipper of LCS-122, received the Medal of Honor.

Today the Landing Craft Support Museum [usslcs102.org] of Vallejo, Calif., serves as the home of the restored LCS-102. “Our purpose,” reads its mission statement, “is to maintain her as a floating museum ship. We aim to educate and inform the public about the role that the 102 and other landing craft support vessels played during the war. LCS-102 is being preserved as a memorial to all LCS sailors, officers and men who made the ultimate sacrifice in service of their country.”

Ron Soodalter is a frequent contributor to several HistoryNet publications. For further reading he recommends Fighting Amphibs: The LCS(L) in World War II, by Donald L. Ball, and Mighty Midgets at War: The Saga of the LCS(L) Ships From Iwo Jima to Vietnam, by Robin L. Reilly.

‘The Maiden Voyage of the 52’

On Nov. 6, 1944, LCS-52 steamed from San Diego Harbor in the company of sister ships 31, 32, 33 and 51. During those first days at sea their crews were, to say the least, abjectly miserable. Among the many stricken with seasickness, Storekeeper Larry “Pops” Cullen of 52 was later moved to eulogize the experience in verse.

I’m telling you of the 52,

That went to sea with her hapless crew.

Not two hours out the waves got rough—

Half the crew had had enough.

They were piled knee-deep in the crowded “head,”

And bodies strewed the deck like dead.

And everywhere the vomit’s stench

From bowsprit back to the anchor winch.

Quite a mess was the 52,

And quite a mess her groaning crew.

All day long the 52

Ploughed the seas with her seasick crew.

And into the night when the waves got high

Most of the crew now wanted to die.

The ship would hit in the trough with a smack

And shudder and roll and grunt and crack.

And shiver and rumble from stem to stern.

The seasick crew for land would yearn.

But undaunted still the 52

Butted the seas the long night through.

The night somehow passed, and some of the men

Felt just a little like living again.

A few still moaned and lay in their sacks

Or stretched on the fantail flat on their backs.

The seas had calmed to a steady roll,

But a day and a night had taken their toll.

And most of the crew was prepared to say

They didn’t know sailors lived this way.

They still felt like they’d always be sick

And would like to be out of the Navy, but quick.

With unslackened speed the 52

Southward carries her seasick crew.

This must go on for three days more

Before the 52 heads for the shore.

Sail on, sail on, O 52,

For I am one of that seasick crew!

This story appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of Military History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.