NASA’s Artemis II moon mission engulfed by debate over its controversial heat shield

As NASA ramps up the preparation to send four people on a trip around the moon and back, a debate is raging among experts and former astronauts over whether the mission’s spacecraft is as safe as the space agency claims.

As soon as March, NASA could launch Artemis II. After being lofted into space by the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, NASA’s Orion capsule will ferry astronauts Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch and Jeremy Hansen in a record-breaking loop around the moon.

NASA is confident that the mission will be successful and safe. But Orion has a potential flaw—in 2022, during Artemis I, NASA’s last (uncrewed) mission to the moon, the Orion capsule’s heat shield came back to Earth with unexpectedly extensive damage.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Heat shields are crucial: when spacecraft reenter Earth’s atmosphere, they heat up, burning through the sky like a shooting star. Without a protective layer, any living thing inside a returning spacecraft would be exposed to temperatures about half as hot as the surface of the sun, or 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,760 degrees Celsius).

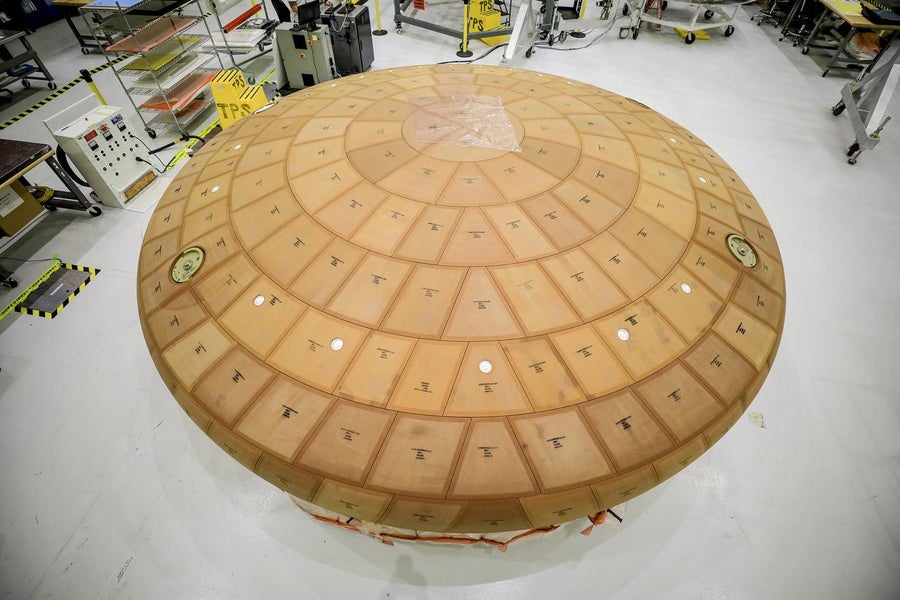

In Orion’s case, the heat shield is made of Avcoat—the same material that protected the Apollo capsules, with a key structural difference. For the Apollo spacecraft, the heat shield had a honeycomblike structure with more than 360,000 cells, each of which was filled with Avcoat. Orion’s heat shield, by contrast, is made up of just under 200 large tiles of Avcoat. Together, they form a 16.5-foot-diameter panel that’s bolted onto the spacecraft.

A close-up of the charred heat shield from the returned Apollo 16 Command Module, showing its honeycomb structure.

aroundtheworld.photography/Alamy

“The heat shield on [the] Artemis II Orion capsule is an example of taking a legacy material that was vetted and basically making the same material but in a little bit of a different way,” says Ed Pope, an advanced materials expert and heat shield engineer. In turn, that opened the door to new, unaccounted for risks with the material, he says.

NASA opted to use Avcoat to protect Artemis in 2009, says Jordan Bimm, a space historian at the University of Chicago. “That’s a long time ago, 2009, and it’s interesting that there have been so few actual reentry tests,” Bimm says. “We’re here on the eve of launch, and there are open questions about [the heat shield].”

NASA has extensively tested Avcoat’s performance in ground-based lab tests and simulations, but a true reentry test is the “gold standard,” according to Bimm—and Orion’s Avcoat heat shield has experienced only one reentry test: Artemis I.

During the Artemis I reentry, big, brick-like chunks of Avcoat broke off the Orion capsule, leaving the heat shield pockmarked with charred holes. NASA’s office of the inspector general released a report of the damage in 2024 and concluded that any astronauts onboard would probably have been alright.

Artemis I’s damaged heat shield.

“When I saw those pictures, I knew this whole design is wrong,” Pope says, suggesting that the difference lay in the decision to tweak the heat shield’s structure from the Apollo-era design.

Importantly, by the time the report came out, it was too late for NASA to replace the heat shield for Artemis II without significantly delaying the mission—which is already running years behind—or adding to its budget.

Instead, NASA decided to alter Orion’s reentry path so that the Artemis II heat shield would encounter more stress but for far less time compared with Artemis I. The change, according to the agency, will ensure Artemis II is not a repeat of Artemis I. But, Bimm says, by leaving the heat shield itself unaltered, the agency has not helped to dispel any worries.

Pope says the fix also doesn’t fully account for the risks with the heat shield that Artemis I revealed.

“We know there is an added risk that can be addressed, and we even know how to address it, because Artemis III is going to have a different heat shield,” Pope says, referring to the Artemis mission in which astronauts will be delivered to the moon’s surface. “They know they can make a different heat shield, and they have made it or are making it, but that would have induced even further schedule slippage.”

NASA is adamant that Artemis II will only fly when ready—and that the heat shield on the mission’s Orion spacecraft is safe enough to successfully return the four astronauts onboard to Earth, even if it experiences dama. “From a risk perspective, we feel very confident,” said a senior NASA official at a September 2025 press conference about Artemis II.

Artemis II’s heat shield.

NASA administrator Jared Isaacman echoed that sentiment in a January social media post, writing that “human spaceflight will always involve uncertainty” but that NASA is committed to using science, technology and engineering to mitigate risk. “Crew safety remains our foremost priority at NASA. With this disciplined approach in place every step of the way, we are moving steadily—and confidently—toward sending astronauts farther into space than ever before.”

And at a press conference in early January, Isaacman said that NASA has “full confidence in the Orion spacecraft and its heat shield, grounded in rigorous analysis and the work of exceptional engineers who followed the data throughout the process.”

Pope points out that space is a risky business, no matter how much work you do to mitigate those risks. But that’s exactly why worries over the heat shield have persisted, he says: NASA didn’t change the material or test it again on an uncrewed mission.

“I think it is probable that the Artemis II mission will end successfully because I don’t believe that somehow the risk here is over 50 percent,” Pope says. “But I think the risk of a heat shield failure is somewhere in the [range of] one out of five to one out of 50.”

Still, the fact that former astronauts have been among those criticizing the agency for using the potentially flawed heat shield for Artemis II, a mission to send humans farther into space than ever before, has caught significant media attention. Among the most vocal is Charles Camarda, a former NASA astronaut who flew onboard the now defunct Space Shuttle Discovery in 2005 on NASA’s first crewed mission, following 2003’s Space Shuttle Columbia disaster, which killed seven astronauts. Notably, the Columbia tragedy arose after a piece of insulation foam around the Space Shuttle’s external tank broke off and struck the spacecraft’s thermal protection system tiles—penetrating its heat shield and causing the craft to break apart on re-entry.

“This discourse of anxiety and worry is based on a history of disasters,” says Bimm, nodding to Columbia and the 1986 Challenger disaster, which also killed seven astronauts. “It’s not without precedent.”

Camarda has repeatedly voiced his concerns over NASA’s decision to use the same heat shield for Artemis II that had been used for Artemis I without testing the new trajectory on an uncrewed mission first. But former astronaut Danny Olivas, who took part in NASA’s review of what happened to Artemis I’s heat shield, has pushed back, saying NASA has done enough work to make any risk the heat shield poses “acceptable.”

“None of the fatal disasters in NASA’s history have been caused by the astronauts,” Bimm says. “It has never been operator error. It’s because of design and system choices, and it’s the sort of, larger, big science, socio-technical system that got them.”