Most Countries Are Reducing Deaths from Heart Disease, Cancer and Diabetes

September 15, 2025

3 min read

Death Rates from Chronic Diseases Dropped in Most Countries

A report finds that death rates from cancer and heart disease have declined since 2010 in roughly 150 countries. Experts explain potential reasons why

Chiyoda ward in Tokyo was the first municipal government in Japan to prohibit smoking on sidewalks.

The chance of dying from chronic illnesses such as heart disease, cancer and diabetes declined in four out of five countries between 2010 and 2019, finds a study of 185 countries published in The Lancet today.

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading cause of death globally. The United Nations has set the goal of reducing deaths from these diseases by one-third by 2030.

The latest study is the first to investigate the change in NCD mortality across countries. It finds that, from 2010 to 2019, the probability of dying from an NCD before the age of 80 fell in 152 countries for women and in 147 countries for men.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Despite these gains, more than half of the countries saw slower declines in the 2010s compared with the previous decade. “Around the beginning of the millennium, we saw significantly lowered mortality rates, but despite political attention suddenly over the last decade, things are not doing as well as before,” says Majid Ezzati, a co-author and global-health researcher at Imperial College London.

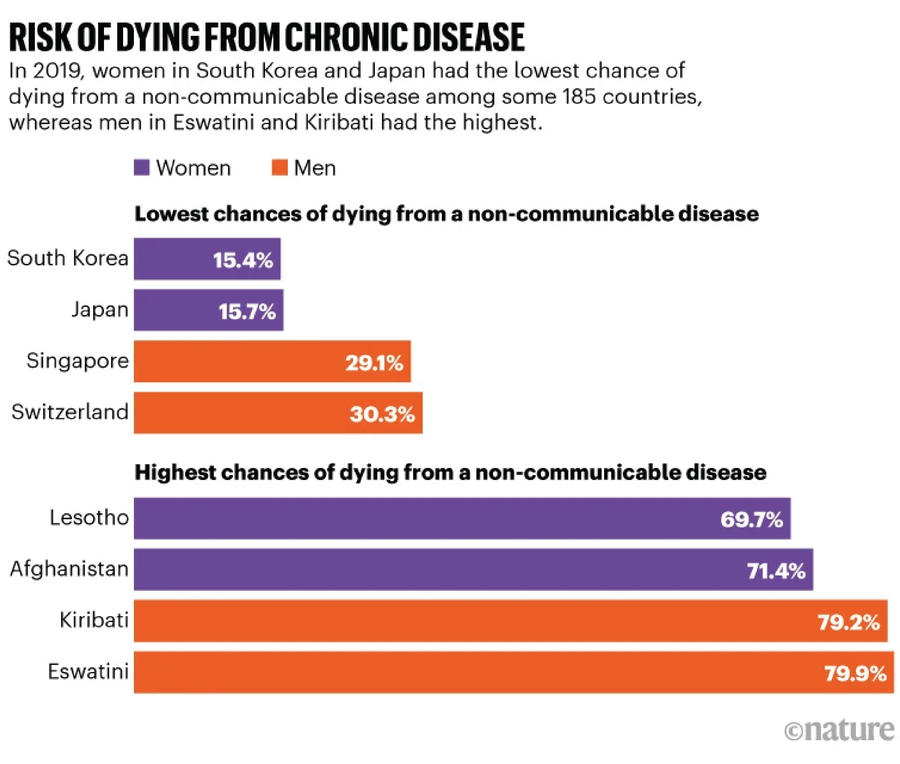

In 2019, women in Japan and men in Singapore had the lowest risk of dying from a NCD among the countries studied, while women in Afghanistan and men in Eswatini had the highest (see ‘Risk of dying from chronic disease’).

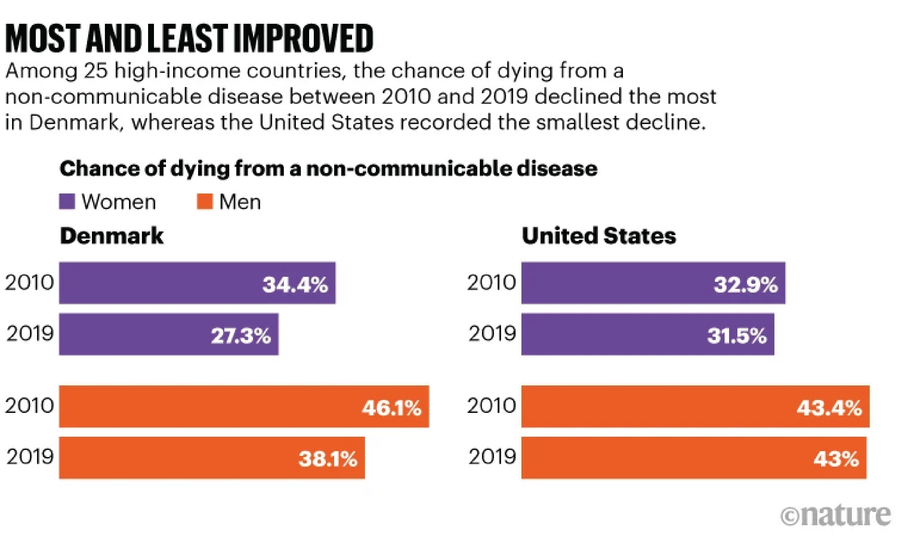

All 25 high-income countries in the data set saw declines in NCD mortality between 2010 and 2019, with Denmark recording the largest drop for both sexes and the United States the smallest (see ‘Most and least improved’). China, Egypt, Nigeria, Russia and Brazil had a reduction in chronic-disease deaths, whereas India and Papua New Guinea experienced an increase in NCD deaths over the same period.

Veronica Le Nevez, a public-policy specialist at the George Institute for Global Health in Sydney, Australia, says that the report finds the biggest drivers of improvements in death rates were embedding better treatments and preventions in health-care systems, the widespread adoption of statins and hypertensives to lower the risk of heart attack and stroke and the development of vaccines for hepatitis and cervical cancer.

Government restrictions on tobacco and alcohol have also helped to reduce mortality from diseases linked to their use, such as lung cancer and alcohol-use disorder.

Slow down

Ezzati says that the slowdown between 2010 and 2019 could be because of underfunding, poor targeting of vulnerable populations and a lack of clarity in public-health priorities. In many countries, proven interventions to reduce chronic-disease deaths, such as treatment for high-blood pressure and diabetes and cancer screening, have stagnated or even declined since 2010, despite being low-cost and highly effective, he says. Government restrictions on tobacco and alcohol have also lost momentum in many regions, he adds.

“It is disappointing to note that liver cancer contributed towards higher NCD mortality in most countries despite the strong evidence base and availability of alcohol-control policies,” says Naomi Gibbs, a health economist at University of York, UK.

High-income countries such as the United States and Germany saw a decline in improvements because of a rise in neuropsychiatric conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease, other dementias and alcohol-use disorders. “Mortality from Alzheimer’s disease and dementias increased in 65% of countries, and in 90% of high-income countries,” says Le Nevez. Accelerated funding and the implementation of programmes addressing these conditions is needed urgently, she adds.

Le Nevez notes that the study looked only at mortality, but many people live with an NCD, and often with more than one chronic condition, for many years. “We need to also consider how to live well with chronic disease,” she says.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on September 10, 2025.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.