Civil War Art, in the Round and Mobile

As it is today, entertainment was an important part of life in the 19th century—and for soldiers stationed far from home, even the smallest distraction from homesickness was essential. Limited options were readily available, however. Antebellum audiences in some regions, for example, could enjoy a visit by the traveling Zouaves of Inkerman—French Zouaves who had teamed with their British allies during the Crimean War to defeat Imperial Russian forces at the November 1854 Battle of Inkerman. Those Gallic troops donned exotic uniforms patterned after ones worn by French Algerian soldiers, a style of dress that found immediate favor among military forces on both sides in the upcoming Civil War.

In early 1861, a newspaper in Memphis, Tenn., touted the arrival of the Zouaves of Inkerman in a newly built theater, enticing audiences with notice that the shows were to run for only two days and would be a “grand military spectacle in five and seven Acts Tableaux,” that the performance would “commence with the French Vaudeville of La Corde Sensible” and that “Zouave Frederick” would perform La Marseillaise. At the time, such live-action shows involving military drill, fancy costumes, and historical recitations by dramatic actors were cutting-edge entertainment.

Prior to the Civil War, technology known as “polyoramas” catapulted to fame as a feature at Niblo’s Garden in New York City. Founder William Niblo had emigrated from Ireland to New York in the early 19th century, and after a short stint working at a small tavern, he bought his own facility and dubbed it Bank Coffee House, eventually expanding his empire to include the Columbian Gardens, an all-weather entertainment facility. Both locales would host plays, concerts, and eventually polyoramas.

Polyoramas enjoyed increased exposure as the century progressed. Often called “Moving Panoramas,” they were 360-degree panoramic paintings to be shown in cylindrical buildings constructed specifically for that purpose. Special equipment would maneuver the painting in a circle before a seated audience.

What caused the medium’s popularity to grow was an owner’s ability to transport the apparatus to other cities across the nation, and innovations that eliminated the need to operate only in a round structure. Replacing the larger viewing area was a box-like window behind which the canvas would rotate. Long strips of painted canvas would be moved across the stage horizontally using a cranking mechanism, visible through the “window” opening. To not be distractions, the device and musicians were secreted away.

Initially, polyoramas portrayed signature battles from across the ocean, such as Waterloo or the 1805 naval battle of Trafalgar. Wagons would transport the large paintings and corresponding hardware, along with a small crew, to each venue. Because of Niblo’s widespread name recognition, each traveling group would tout a partnership with him, whether real or not. Viewings in a particular city would usually last about a week.

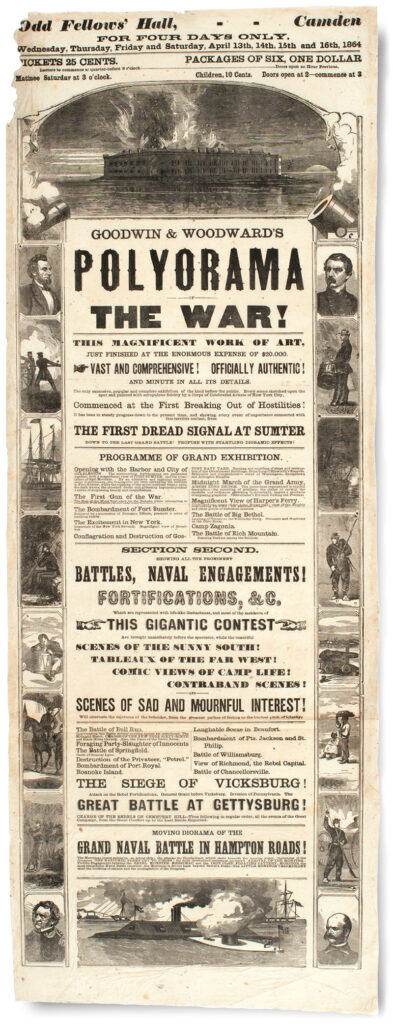

A New View of War

(Library Company of Philadelphia)

Once the Civil War began, the subject matter of the polyoramas increased substantially. The variety of battles available for display with a war in their backyard allowed viewers more opportunity to learn what had really transpired at the event. As one such demonstration beginning May 11, 1863, in Cleveland, Ohio, was advertised:

“This is the Most Complete Exhibition Now Before the Public! Accurate, Authentic & Comprehensive, from the First Dread Signal at Sumter to the Battle of Fredericksburg, Profuse with Dioramic Effects, entirely new and on a scale magnificent and surprising The Thunder of Artillery and The Din of the Battle Field are realized with a vividness so nearly approaching Reality that the audience seem to realize the work of carnage as if the scene of life and death was Actually Before Them.”

The group would play “popular and appropriate music” that would accompany each painting, in addition to a “Patriotic Descriptive Lecture” delivered by “Mr. John Davies (late of the Boston Museum) whose delineations of these pictures have won for him the appreciation of many thousands in the cities of New York, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Cleveland and Chicago, where they have been exhibited with great success and pronounced unrivaled and unapproachable.” This particular polyorama company would occasionally be accompanied by Miss Viola, the “highly celebrated Patriotic Ballad Singer” and Mrs. Hattie Pomeroy, the “Popular Songstress.”

Traveling shows were a success across the nation and beyond during the war. In January 1864, for example, “Honolulu residents learned about the Civil War by viewing J.W. Wilder & Co.’s Polyorama depicting ‘The Terrible Rebellion.’ Narration and music accompanied a series of interlocking painted images drawn across the stage of the Royal Hawaiian Theater.”

Advertisements promised a survey of the war, east to west, land and sea, including the “Great Naval Combat between the Iron-Clad Monsters, The Monitor and The Merrimac!” Viewers would be informed of “key political figures, comic scenes in camp life, and sad and mournful events, all for just $.50.”

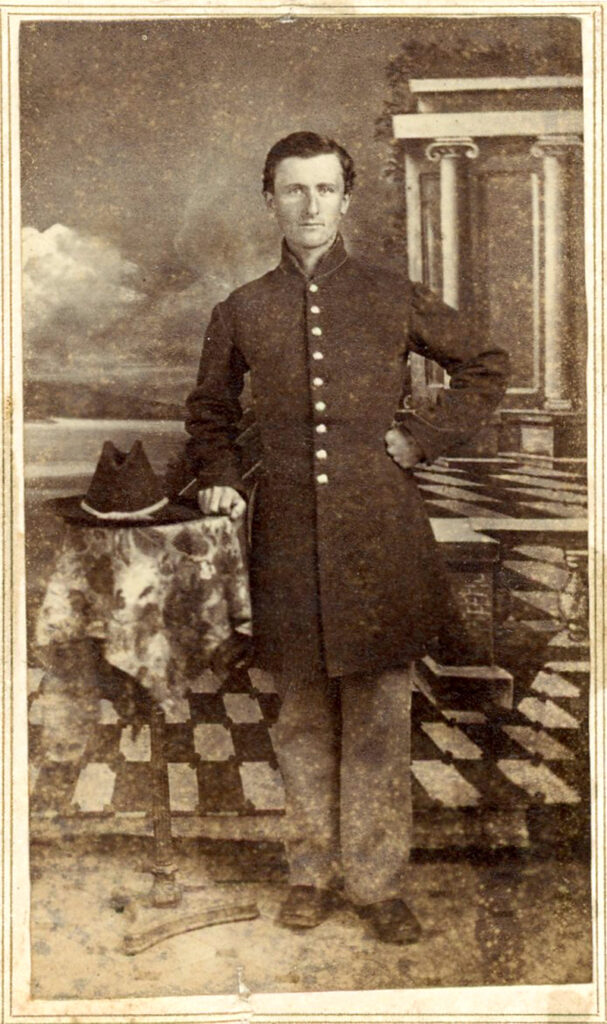

(Michael Cunningham)

Some portrayals made a strong impression on the audience. One such individual was Lewis Josselyn, a shoemaker-turned-private in the 38th Massachusetts Infantry stationed in Baton Rouge, La., who wrote a letter to his mother after seeing a polyorama presentation in town. The 21-year-old Josselyn provided a wonderful blow-by-blow account of the legendary March 9, 1862, naval battle at Hampton Roads, Va:

“Last night Butt and I went to a show that is now here for a few nights. It was a Poly[o]rama (they call it) of the war from New York. It was paintings the same as a panorama or I could not see any difference in it. It was the best show of the kind that I ever saw. The paintings were as natural as life. One of the pieces was a fight between the Monitor and Merrimack. It first showed the Cumberland (the one that Hugh was in) and Congress in the Hampton Roads rocking in the water. The waves looked as if it was the sea itself. Then in steamed the Merrimack, going up to the Congress as if to run into and sink her, but the Congress then was aground and she dare not venture up to her, so she turns upon the Cumberland and runs into her, and then runs back and tries it again, this time making a hole in the Cumberland, and she sinks, with her colors still flying at the mast.

“The Monitor now comes in, and engages the Merrimack. She finally finds the Yankee cheese box too much for her and she has to retreat. As she does so, she fires a shell at the Congress and sets it on fire and is destroyed. This was done the best of anything of the kind I ever saw. I go to the theater every few nights. They now have it closed to us and our boys go as guard. I could go every night if I wanted to, but I don’t want to go every night unless they are going to play something pretty good – better than generally is for it is a poor theatre.”

Some shows became semi-permanent fixtures in large cities. Cutting’s Polyorama of the War was so popular in New Orleans that the manager of the St. Charles Theatre announced that Mr. Cutting would be giving presentations there “until further notice.”

Not all the viewers, however, were enamored with these shows, such as this mixed review in the Tunkhannock, Pa., newspaper in 1865:

“Hasty & Twombly spread what they called a Polyorama of the War, before a crowd of the curious, on Wednesday and Thursday evening last. It was evidently meant to represent a fight of some kind, but whether some of the great battles of our civil war, of the Crimean war or a Tunkhannock plug muss, we could not determine. Their closing scene, ‘Unnamed Heroes,’ was good, and worth the price of admission; the rest was a bore.”

While polyorama shows like the one Private Josselyn saw in Baton Rouge were captivating, others were duds for assorted reasons, or only partially interesting like the aforementioned Tunkhannock presentation. To offset potentially dull shows with poorly skilled narrators, uninspiring music, or ineffective paintings, additions were sometimes included to augment interest—though some demonstrations echoed a P.T. Barnum sideshow. For example, Morton & Co.’s “Polyorama of the Rebellion” offered viewing of “The Famous Little Zouave Twins”—an infant drummer and fifer “who led the decisive and immortal charge of the 19th Illinois at Murfreesboro, Tenn. They appear in full costume and go through the Zouave drill at the bugle call. Bayonet, small broad-sword exercise, and at one time play upon the instruments which compose a full band…” This presentation in Red Wing, Minn., was promoted heavily by the local press as “highly spoken of” and urged citizens to “Go and see it!” Viewings in a particular city would usually last about a week.

Rise of the Cycloramas

After the war, audience attendance waned as people grew tired of seeing reminders of the hardships of war. The lull did not last too long, however, with a resurgence in the 1880s. New and old companies rose to the occasion and started traveling the country again. Traditional round buildings also reappeared, but now audiences would stand at the center as the painting rotated before them.

The basic premise of the display slightly changed along with the name of polyorama being switched to cyclorama, although they were very similar in nature. A cyclorama did have the addition of dioramas of the contested battle areas to bolster the visual effects.

(National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

In 1885, the Philadelphia Panorama Company constructed a cyclorama of the Battle of Chattanooga in both Philadelphia and Kansas City, Mo. A few years later, a cyclorama was constructed and painted of the devastating 1876 Battle of Little Bighorn focusing on the loss of George Armstrong Custer and his command.

Over the next decade, hundreds of cycloramas were created, of which only about 30 survive today. The most realistic cyclorama was probably the re-creation of the classic story of Ben-Hur, written by former Union Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace. Real horses and chariots were used within the background of a cyclorama painting. This method exceeded all previous incarnations to the medium and allowed the pubic to experience the best example in lieu of actually being at the dramatic fictional event written in the book.

(Gettysburg National Military Park, National Park Service)

Two cycloramas depicting Civil War events still exist today and are open to the public: one representing the monumental July 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, the other the July 1864 Battle of Atlanta. The painting of the Gettysburg conflict was the work of French artist Paul Dominique Philippoteaux, who concentrated his efforts on the climactic Confederate attack famously known as Pickett’s Charge. Once the Frenchman finished his artwork, the painting stood 22 feet high and 279 feet in circumference.

Among veterans of the battle whom Philippoteaux interviewed to provide more realistic scenes were Union Generals Winfield S. Hancock, Abner Doubleday, O.O. Howard, and Alexander S. Webb. For further detail, Philippoteaux also took photographs of the terrain upon which the charge took place. Realism was considered essential, as the cyclorama included artifacts and sculptures, including stone walls, fences, and trees. Recently restored, it is currently on display at the Gettysburg National Military Park Museum and Visitors Center.

The Battle of Atlanta Cyclorama, 49 feet high and more than 100 yards long, was also recently restored. Augmented by modern technology, it is on display at the Atlanta History Center.

The American Panorama Company of Milwaukee hired 17 German artists with a penchant for beer to create the painting. It took the painters nearly five months and many cases of beer to complete the detailed painting. It debuted in Minneapolis in 1886. Due to its initial location in Minnesota and the efforts to attract Northern tourists, the focus of the events during the Battle of Atlanta concentrated on the Northern perspective, with highlighted Union military personnel and the Confederate side painted a bit more shadowy and vague. When the massive painting was relocated to Atlanta, it was billed locally as “the only Confederate victory ever painted” to appeal to audiences in its new Southern venue, although the original battle was certainly not victorious for the boys in gray.

Richard H. Holloway is a frequent ACW contributor. Check out his article on George Custer at historynet.com/east-west-rivalry-civil-war.