breaking the stigma of substance-use disorders in academia

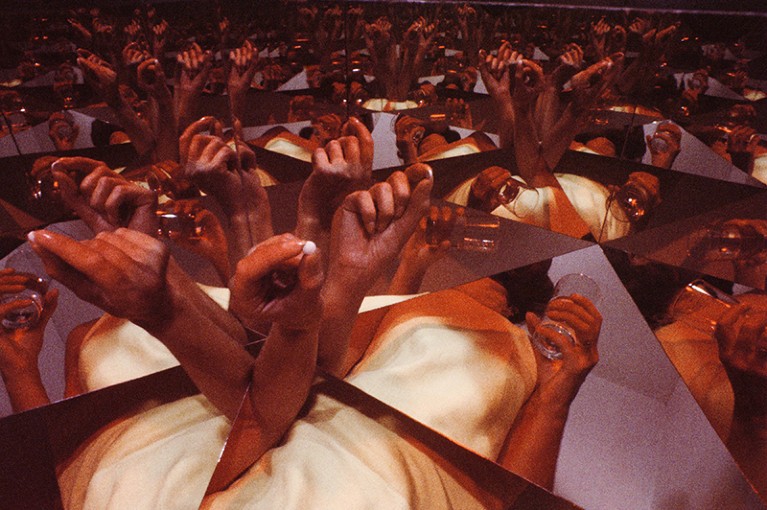

Credit: David Attie/Getty

In 2003, Wendy Dossett chaired an international symposium at a UK university. “I don’t remember chairing it. I know that I did, but I don’t remember anything that happened,” she says.

At the time, she did not think that she had an alcohol problem. “I thought I could not possibly be an alcoholic — I had a PhD, I was holding down a high-pressure academic job, I didn’t fit the image of what an alcoholic is,” she remembers. It took 2 years for her to seek treatment, and another 14 years before she told her employers at the University of Chester, UK, where she worked in religious studies, that she was in recovery.

Science careers and mental health

Dossett is not alone, but academics who struggle with substance-use disorders, or who are recovering from them, are often hidden from view. These conditions affect a person’s brain and behaviour as a result of uncontrolled use of alcohol, prescription medications or illegal drugs (see ‘What is drug or alcohol-use disorder?’).

Evidence shows that substance-use disorders are chronic diseases — involving changes to the brain’s systems for reward, stress and control — rather than a choice (see go.nature.com/4tbcczf).

Dependency disorders are present in people of all professions, but academics — who often set their own schedules and work regularly in isolation — are often good at concealing them, or might not realize that they have a problem. Moreover, the competitive environment and concerns about professional reputations, along with a fear of being fired, deter many from disclosing their illness. But some institutions are pioneering programmes to support staff.

The World Health Organization estimates that, in 2024, 400 million people worldwide, or 7% of the global population aged 15 and over, were living with alcohol-use disorder. Meanwhile, a report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime states that, in 2022, more than 64 million people had drug-use disorders, and yet only one in 11 were receiving treatment. But there is little information on prevalence among faculty members.

One reason for this, says Marissa Edwards, an organizational psychology researcher at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, is that universities and academics are uncomfortable talking about these disorders. “Addiction is still one of those last taboo topics that is not really shared or discussed,” she says.

‘No one is talking about it’

When Victoria Burns told her dean at the University of Calgary in Canada that she was in recovery from alcohol-use disorder, he said she was only the second staff member to come forward in his 26 years in the position.

“We know that stress leave is on the rise, and substance use is part of that. It’s happening, but no one is talking about it,” says Burns, who studies homelessness, stigma, addiction and recovery.

In 2021, Burns and her colleagues published one of the few studies looking at substance-use disorders in faculty members (V. F. Burns et al. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 7274; 2021). They interviewed 16 people who were deans or campus mental-health professionals at Canadian universities, with a combined 300 years of service, about instances of faculty members disclosing substance-use disorders. Across all 16, a total of only 3 such disclosures had been made to them during their careers, all regarding alcohol use.

“Every single one of us has seen that professor at the departmental reception who routinely has a few too many,” says Bryan Pitts, a historian at the University of California, Los Angeles, who is in recovery from a substance-use disorder. “I don’t think anyone’s going to be shocked to discover that a colleague is keeping a bottle of whisky in their desk drawer,” but it’s not talked about openly, he says.

Victoria Burns works to establish recovery programmes on campuses across Alberta, Canada.Credit: Victoria Burns

Tim Brennan, vice-president for medical and academic affairs at the American College of Academic Addiction Medicine, who is based in New York City, says academics are no more susceptible to substance-use disorders than are those in other professions. “I’ve seen addiction in every occupation, whether it’s people in manual jobs such as building skyscrapers, or in fields that have particularly high mental stress, like people on Wall Street managing millions of dollars,” he adds.

However, there is a strong link between substance-use disorders and mental-health conditions — including anxiety and depression, which are common among academic staff. Studies of faculty members, staff and students in the United Kingdom, the United States and continental Europe show that a large proportion are struggling with a range of mental-health issues, including depression and burnout. For instance, 64% of faculty members surveyed at 8 US institutions reported feeling work-related burnout in the 2022–23 academic year (see go.nature.com/4tduwye).

Reconsidering the role of alcohol in the scientific workplace

It’s rare for someone to develop a problem if taking a drug or drinking alcohol is just for pleasure, says Ed Day, a clinical psychiatrist and researcher at the University of Birmingham, UK, who was appointed as the UK government’s national drug-recovery champion in 2019 to develop best practice around addiction recovery. “You tend to develop a problem if it’s an adaptive, rational way of coping with some other issue in your life, such as stress. Then it gets out of control and becomes something of its own,” he says.

Pitts thinks he was always prone to substance misuse, starting with alcohol, which was ubiquitous and part of the culture during his university studies more than a decade ago. He remembers a faculty member always arriving at a weekly graduate seminar “with two six-packs in hand” and other regular outings that led him to drink multiple times each week. Today, many institutions are rethinking campus alcohol policies, as are conference organizers. According to a 2022 Nature poll, however, 68% of academics surveyed did not want to see alcohol banned at scientific meetings (see Nature https://doi.org/nw76; 2022).

Pitts tried other drugs during his PhD studies, and psychostimulants became his escape. “I would spend days, weeks, months at a time being the perfect little graduate student and drugs were my way to completely check out,” he says. His flexible schedule meant that he could spend days at a time high without anyone noticing.

At one point, Dossett lived in a “mouldy caravan” for four months and showered on campus, but still her colleagues and superiors did not notice. “I really tried to hide it as much as I could,” she recalls, saying the flexible hours and self-directed academic lifestyle allowed her to disguise her dependency in a way that would have been difficult in a more nine-to-five profession.

‘Sticky’ stigma

Stigma prevents many people from accessing help. “There is an assumption that people with addictions are making a choice, that they’re weak, misguided and selfish,” says Dossett. “It’s a particularly sticky stigma and that prevents people from being able to be honest about it.”

Although society has begun to realize that “you can’t just tell a depressed person to cheer up, I don’t think that as a society we’re at a point where we recognize addiction as an illness”, says Edwards. “That’s a big part of the stigma.”

This plays out in several ways. Those with a disorder might internalize the stigma, which can exacerbate their substance-use cycle. They might also be less likely to access help because of how they think they will be perceived, and sometimes managers and institutions develop policies that are not appropriate for dealing with these conditions.

“Even though post-secondary institutions are known to be, in theory, progressive, when it comes to our own struggles as academics, there’s an expectation that we should not show any sign of weakness,” says Burns. Those struggling with a substance-use disorder worry that it will reflect poorly on them and harm their job prospects.

Religious-studies researcher Wendy Dossett says the stigma associated with substance-use disorders is “particularly sticky” and stops academics from disclosing their struggles and recoveries.Credit: Wendy Dossett

“People are scared and they are full of shame” and might not want to admit to having an addiction diagnosis or have it on their record, she says. This is one of the reasons for the lack of data on substance-use disorders among faculty members. If people do access help, their addiction is often included in or masked by a mental-health diagnosis, she says.

For some, seeking help from their university could result in them losing their jobs. This is what Pitts feared, because one of his previous institutions had required him to sign an affidavit stating that he would not consume illegal drugs during his employment. “It didn’t stop me, but it made it very clear that it would be best to hide [my usage],” he says. By contrast, his current institution is part of the University of California system, which explicitly offers support to staff struggling with substance misuse, something that has helped Pitts in his recovery.

When one researcher, who did not wish to name her institution, raised the issue of starting a programme for faculty members affected by substance misuse, she was told that no one at her institution was in recovery from addiction because of a zero-tolerance policy regarding drugs and alcohol. “And I thought, ‘That’s just insane. They need to know there are quite a few of us — among staff, among students — and this zero-tolerance attitude does nothing but feed stigma and prevent people seeking help.”

Two-thirds of scientists want to keep alcohol at conferences

In some countries, such as Canada, substance-use disorders qualify as a protected characteristic, which means that a person cannot be discriminated against for having that attribute. Other examples include age, race and gender. But such protection for the disorders is not the case everywhere — in the United States, only those in recovery for substance-use disorders are protected; in the United Kingdom, no such protected status exists.