An SAS Rescue Mission Mission Gone Wrong

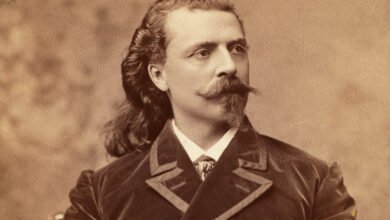

Norman Crockatt is not a well-known name, but the British intelligence officer was responsible for one of the most controversial decisions of World War II.

When the War Office in London created Military Intelligence Section 9 (MI9) on December 23, 1939, it chose the 45-year-old Crockatt to head the new organization. The former head of the London Stock Exchange, he was seen as “the right sort of chap” for the post despite his scant experience in military intelligence.

MI9’s mission was to help British military personnel escape and evade the enemy. That might mean smuggling maps and miniature compasses to prisoners of war held in Nazi camps or assisting shot-down airmen in enemy territory to evade capture and get back to Britain or Allied-controlled territory. MI9 was a small branch of British intelligence, but in June 1943 Crockatt had the responsibility of making a momentous decision about the fate of 80,000 Allied POWs incarcerated in Italian prison camps. The Allies were gearing up to invade Italy and Crockatt had to decide whether the POWs there should stay put and wait for the arrival of Allied troops or break out and try to make their own way to freedom.

Crockatt chose the former option, stating in an order issued on June 7, 1943, that “officers commanding prison camps will ensure that prisoners of war remain within camp. Authority is granted to all officers commanding to take necessary disciplinary action to prevent individual prisoners of war attempting to rejoin their own units.” Several factors influenced Crockatt’s final decision. First was the physical state of the prisoners, many of whom were believed to be malnourished after years in captivity. Then there was the prospect of tens of thousands of prisoners on the loose, providing easy targets for vengeful Nazis and fascist Italians loyal to Mussolini. Above all, Crockatt believed that the Allies’ advance north through Italy would be swift and British and American troops would quickly liberate the camps. Why risk a mass breakout and jeopardize the lives of so many men?

(Courtesy www.simondsfamily.me.uk)

To get word to the POWs of what they should do, Crockatt used a secret code contained within the script of a popular BBC program, The Radio Padre, a favorite among the prisoners. But what MI9 didn’t do, remarkably, was inform British prime minister Winston Churchill or his War Cabinet of his decision. From the outset of negotiations with Italy Churchill had made plain his wish to see POWs returned to the Allies once the Armistice came into force. Article 3 of the Italian surrender agreement stipulated that prisoners were to be “immediately turned over to the Allied commander-in-chief and none of these may now or at any time be evacuated to Germany.” When the Armistice was made public on September 8 the Italian War Ministry kept faith with its obligations and told 80,000 Allied prisoners that they were free to leave. But the majority remained in their camps, where they risked falling under the control of the Germans.

Churchill was aghast when he learned of Crockatt’s order for POWs to stay put, but by then it was too late for many prisoners. Contrary to what Crockatt had anticipated, the Germans had wasted little time in taking over most of the camps and were soon hunting the estimated 30,000 who had defied the stay-put command and taken flight.

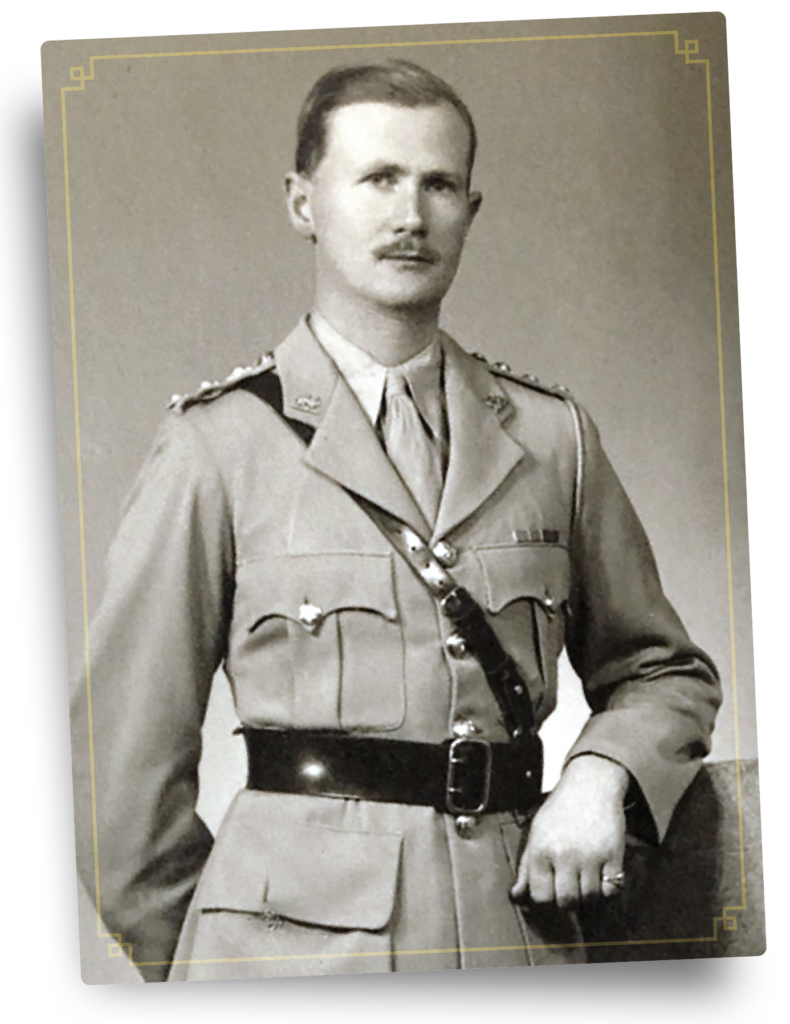

Nothing could be done now to liberate the prisoners in the camps, but Churchill demanded a plan to rescue the fugitives. The man chosen to lead the operation was Lieutenant Colonel Charles “Tony” Simonds, who had joined MI9 in 1941 after fighting alongside General Orde Wingate in what is now Ethiopia. Based in Cairo, Simonds was in charge of A Force, which had responsibility to set up escape lines for Allied prisoners across occupied Europe. Summoned to Allied Forces HQ in Algiers on September 23, Simonds received orders to devise a plan to rescue the thousands of escaped Allied prisoners roaming Italy. He had at his disposal personnel from Britain’s 1st Airborne Division, Second Special Air Service Regiment (2SAS), and Special Operations Executive (SOE), as well as the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS). The mission received the codename Jonquil.

(Courtesy Gavin Mortimer)

Simonds established his headquarters at Brindisi, a port on the eastern heel of the Italian boot, and arranged a meeting with officers from 2SAS, billeted 75 miles northwest in the coastal city of Bari. This elite British special forces unit had been formed in North Africa in 1941 by brothers David and Bill Stirling, and while stationed in Cairo Simonds had heard tales of their effectiveness in raiding Axis targets deep inside their territory. David Stirling had been captured in January 1943 but Bill, in command of 2SAS, sent two of his officers, Major Felix Symes and Captain Peter Power, to Brindisi to discuss the rescue operation.

They arrived on the evening of September 26 and for the next three hours Simonds briefed the SAS officers on the nature of the mission. Standing in front of a large map of the east coast of Italy, Simonds explained that he had divided the region into four areas, from Ancona in the north to Ortona in the south, a range of approximately 100 miles. Simonds defined the role of 2SAS in the operation thus: “In each area two parties will go in, one to be dropped by parachute inland, with the object of sending all P.W.s down to the coast, and one party to land by sea to form a beach party to guide, shepherd, and protect the prisoners, and also to supervise their embarkation after having signaled the boats.” There were seven soldiers in each party, and the boats were vessels that would rendezvous off the beaches to take on the escapees.

Furthermore, Simonds planned to have two other parties landed in the most southerly of the four areas to collect a large number of prisoners known to have gathered close to the town of Chieti. Attached to each A Force team would be an Italian speaker to question villagers about the prisoners’ whereabouts.

Simonds recruited a handful of interpreters locally, but he also could exploit the linguistic skills of the American OSS, which had a sub-unit called the Operational Group (OG) with the role of organizing, equipping, and training indigenous populations to fight common enemies. Unlike Britain in the first half of the 20th century, America had a “melting pot” society that enabled the OSS to recruit operatives from Chinese, Japanese, Greek, Norwegian, Italian, and other communities. The standard OG comprised four officers and 30 enlisted men, and the Italian unit was commanded by 1st Lieutenant Peter Sauro. Born in Yonkers, New York, to Italian parents, the 31-year-old Sauro had been a tree surgeon before the war; he was small and past his physical prime, but he had a good grasp of his ancestral language.

Sauro and his section reached OSS headquarters in Algiers on September 8, the day that Italy officially surrendered. Designated Unit A, First Contingent, Operational Groups, 2677th Headquarters Company Experimental (Provisional) AFHQ, Sauro’s OG was the first of its kind to be activated and spent the next two weeks in parachute training.

On September 25 OSS HQ informed Sauro of the A Force mission to round up escaped Allied prisoners in Italy. He had 24 hours to select 18 men for the operation and equip them as necessary. They received the codename Simcol. Once they had reached Italy, Sauro’s team of Italian speakers traveled by vehicle to Bari, where A Force had established its new base and where Simonds introduced Sauro to the SAS officers. Simonds asked him to provide one of his men to each of the four SAS parachute parties and another to each of the five teams who would land by fishing boat. Sauro and his remaining nine members of the OG would take part in a parachute operation independent of the British.

(Courtesy Gavin Mortimer)

Sauro’s team left Bari airfield in the late afternoon of October 2 for the short flight north to Catignano, a village 20 miles inland from Pescara. They parachuted onto the drop zone without incident.

A few hours after Sauro’s party had flown from Bari, a fleet of eight schooners sailed out of the city’s port under the command of SAS Captain Peter Power, a 32-year-old Irishman. Their voyage up the eastern coast took them longer than expected because of fierce fighting at Termoli, 125 miles north of Bari, where for three days a battle raged between the British 78th Infantry Division and the German 1st Parachute Division. At Termoli, Power and his 12 men exchanged the schooners for LSI’s (Landing Ship, Infantry) and continued on their mission, finally going ashore at 2:00 a.m. on October 7 at Grottammare, 100 miles north of Termoli and 50 miles north of Sauro and his men. They had landed several miles south of their intended disembarkation point so they marched north overnight through torrential rain to reach the correct stretch of coast.

On the night of October 9-10 Power signaled ashore a naval dinghy stocked with supplies. It also brought the message that it would not be back again “until the nights of October 24/25 and 25/26 owing to the moon, and that all prisoners must be embarked on these nights.” Power’s party had a formidable task ahead of them. Deep inside enemy territory, without any wireless sets—none had been provided despite repeated requests—they had no means of extraction for a fortnight.

Power divided his force into four groups, three of which would search the surrounding countryside to the north, west and south. The fourth party, under the command of Sergeant Major Bill Marshall, would remain by the coast to receive prisoners as they were brought in, and conduct a sweep of the coastal area for any other escapees.

When he set off north on October 10 Power had two men with him: Bob Tong, a 20-year-old private from Shropshire, and sergeant Joe Marino, one of Sauro’s OG interpreters. Power kept a daily tally of their accomplishments in his log. On the evening of October 11, he noted that they contacted 14 prisoners, including two South African officers. They next day, “British officers arrived at 11.00 hrs and told us there were a number of prisoners near Corridonia.” On October 13 they contacted another six prisoners, and when they reached the Corridonia area the next day they found a prisoner who said he knew of 30 more. They found nine more on October 15, and on the 16th made contact with a communist who was hiding about 30 escapees.

On the return march to the beach, Power collected more prisoners, all of whom he corralled into a farmhouse about two miles from the coast under the supervision of Tong and Marino. When he reached Marshall’s base camp on October 20 Power found 34 more POWs that Marshall and his men had collected over the week. “All going well,” wrote Power in his journal. Now they just had to sit tight and wait for the naval vessels to arrive in four days.

(United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, gift of Miriam Davenport Ebel; IWM HU 43228)

Their fortunes turned the next morning. A routine German patrol spotted Marshall’s base camp and in the ensuing firefight two SAS were captured and a number of Germans killed and wounded. On hearing the firing, Power shepherded the POWs from the farmhouse into a ravine where they remained for the day. To make matters worse, Sergeant Marino was unwell, a condition Power described in his journal as “delayed V.D.”

Fortunately, the Germans did not launch a follow-up operation. Power posted lookouts on the coastal road but they spotted nothing untoward. On October 23 SAS parties from the other three operational areas began arriving with their haul of wandering POWs. In total, noted Power, by the morning of the 24th they had “about three or four hundred prisoners.” Many were excited at the prospect of their impending salvation, while others were tired, hungry, and irritable. Months and years as prisoners and weeks as fugitives had eroded much of their military discipline. Eventually, however, the SAS led them to within a few hundred yards of the beach.

The boat was scheduled to arrive at half past midnight on October 25, and Power’s instructions to the prisoners were to “come in parties not larger than three.” Marino, though still debilitated by illness, was to act as their dispatcher. Power and Tong started out for the beach at 11:40 p.m. They had hardly arrived before they heard “bursts of automatic fire” and then the unmistakeable sound of trucks arriving. Panicking, the gathered POWs “stampeded back into the hills.” Power and Tong ran north along the beach away from the sound of gunfire. They didn’t know if the two captured SAS men had revealed the evacuation plan under questioning by their captors, or if the Germans had discovered the large number of prisoners on their own.

At daylight Power and Tong continued their trek north, believing the operation had been fatally compromised. But that evening a Royal Naval launch arrived and picked up the SAS party, now under the command of Sergeant Major Bill Marshall and including Joe Marino. After the previous night’s panic only 23 prisoners remained of the 400 brought to the beach. Power and Tong didn’t return to Allied lines for a month, when they sailed into Termoli in a fishing boat piloted by an Italian aviation officer. They brought five POWs with them.

Pete Sauro found himself in a predicament similar to Power’s. Having parachuted into Catignano, Sauro and his men had collected 250 fugitives within 24 hours. The Americans instructed the POWs to muster on the coast at Francavilla, some 20 miles due east from Sauro’s operational base. A naval vessel was supposed to arrive on the nights of October 4, 6, 8, and 10 between midnight and 1:00 a.m. and flash a light every 15 minutes. The password was “Jack London.”

The three other SAS parties scouring the countryside west and south of Pescara were also directing POWs toward Francavilla. In total 600 had reached the coast: 350 British, 200 Yugoslav, and 50 American. But, as the SAS report stated: “They had signalled for four nights (October 4, 6, 8, and 10), without success, though on the fourth night what was believed to have been a German MTB [Motor Torpedo Boat] switched its searchlight on them, and there was an exchange of fire. At the same time a truckload of German troops arrived on the coast road above them.”

(IWM A 20823)

The SAS officer overseeing the evacuation was Captain Raymond Lee. A colorful character who craved excitement, Lee was really a Frenchmen named Raymond Couraud who had won the Croix de Guerre for his actions with the French Foreign Legion in Norway, but later deserted. Arrested, he spent some time in prison, then operated in France as a gangster before joining the SOE and then the SAS under his assumed name.

Lee told the prisoners “to split up and make their way through the lines.” He added that Termoli, 75 miles away, was now in British hands after a three-day battle, and it was safer to travel overland than by sea, where they risked attack from enemy vessels or aircraft.

Sauro issued similar instructions to half of his OSS team, but he and four men continued to scour the area for escaped prisoners, briefing those they found on how to reach Allied lines. Sauro sent three more operatives south on November 3, while he and one other remained searching. Eventually the pair were captured by the Germans.

Captain Lee returned safely to Termoli and volunteered on the night of November 2 to accompany a search and rescue party aboard an Italian MTB. With him was Captain Richard Lewis, a 26-year-old Illinoian and Harvard graduate (who would win the Pulitzer Prize in 1976 for his biography of Edith Wharton), and Augusto Ruffo, an 18-year-old Italian recruited to A Force, whose father was the 6th Duke of Guardia Lombarda. “We were part of an Anglo-American intelligence outfit known in Washington as MIS-X [Military Intelligence Service X] and in London as MI-9,” wrote Lewis in his memoir. “In Italy, we had various cover titles.” One of these was A Force.

The Italian MTB left Termoli and arrived at the rendezvous point off Silvi, seven miles north of Pescara. The vessel’s skipper flashed the recognition signal to shore, where the A Force team, including a British Lieutenant Lyte, spotted it. With them were 12 POWs. Before they could respond to the signal, said Lyte, “machine gun fire and 20mm Breda fire [were] directed at a boat about 1½ miles off shore.”

Lewis and Ruffo were below deck talking on their bunks when the firing started. “I could see tracer bullets flying and could hear shouts of consternation and rapid orders from above,” recalled Lewis. “My young Italian friend, in the midst of a sentence, fell forward from the bunk to lie dead on the floor; a bullet had penetrated the side of the boat and entered his back.”

Lewis flattened himself on the floor as rounds tore through the MTB. When he eventually emerged on deck, he counted the corpses of half a dozen Italian soldiers. “Flames were licking along the railing,” remembered Lewis. “From out in the blackness I could hear the desperate appeal of the Italian sailors who had jumped overboard with their life belts and were floating about crying for help.”

Also in the water was Captain Raymond Lee. Despite being shot in the shoulder, he managed to swim the mile ashore where he was subsequently found by Lyte. Lewis also swam ashore, staggering up the beach and into a dune. “As I watched, exhaustedly, the fire on board reached the torpedo and the boat blew up.”

Lewis was now in the same predicament as the men he had set out to rescue. He struck out south and initially made good progress, relying on the generosity of “kind and unquestioning Italian peasants.” One provided him with an old suit. Although ditching his uniform removed his status as a soldier and raised the possibility that he could be executed as a spy if captured, Lewis believed the tattered suit gave him a better chance of reaching the Allied lines than his combat fatigues. “I was almost within sight of the British lookout posts when I got stuck,” said Lewis. “The long, drawn-out battle of the Sangro River had begun, and the front lines were far too lively for me to attempt to cross.”

Though the British Eighth Army had secured Termoli on October 6, the advance up the east coast of Italy turned into a bloody slog. They finally crossed the Sangro (32 miles northwest of Termoli) on November 23, but it required another five weeks of hard fighting before the 1st Canadian Infantry Division captured the deep-water port of Ortona.

(Courtesy Gavin Mortimer)

As the fighting raged, Lewis hunkered down in a stone cottage near the village of Crecchio, about 12 miles north of the Sangro. “While both armies surged forward and fell back in what, from my fretful vantage point, seemed sheer tactical messiness, I made useless little forays toward making my way to safety, only to retreat each time,” recalled Lewis.

The American finally made it through the lines on December 17, “having swallowed enough raw red wine to give me the requisite courage.” Captain Lee, who had reached Termoli after a 10-day trek, had informed A Force that Lewis had been killed on the MTB, so his arrival was greeted with delight.

Simonds estimated that about 900 former prisoners made the same journey as Lewis and Lee in the autumn of 1943, either by boat or on foot. Some received A Force’s assistance but others relied on their own initiative. It was a disappointing tally considering that an estimated 30,000 prisoners had walked out of their camps in September; in total it is estimated that between 11,000 to 14,000 POWs reached freedom, either in southern Italy or by crossing into neutral Switzerland.

Those involved in the A Force operation quickly pinpointed the major flaw in the operation: the lack of radio communication. Colonel Russell B. Livermore of OSS’s 2677th Headquarters Company had been unable to contact any of the men on Simcol and wrote in his report, “My reaction…is that hereafter we carry out all our own operations and discontinue these ‘joint’ ones with the British.”

Lieutenant Colonel Bill Stirling, commanding officer 2SAS, cited several other reasons for the operation’s ineffectiveness, including the “extremely erratic” timekeeping of the navy that made coordination with the men ashore difficult. But his major complaint echoed Livermore’s: “Signalling arrangements were not satisfactory,” he wrote. “Walkie-Talkies between shore and ship might have been useful. Wireless communications with the base would have prevented the ignorance of the parties of the amended orders issued.”

What frustrated Stirling most was the missed opportunity. “[G]iven a simple plan with a reliable means of communication, and R.Vs [rendezvous], which could be depended on, it might have produced more satisfactory results.” In the end, it remained a lost opportunity.