Luigi Mangione and the Making of a Modern Antihero

He is from a wealthy and prominent Maryland family, the valedictorian of a prestigious private school, an Ivy League graduate. His family and friends speak of him fondly, and they worried about him when he fell off the grid, some months ago. His reading and podcast habits, as gleaned from his Goodreads account and other traces of his online footprint, can be summed up as “declinist conservativism, bro-science and bro-history, simultaneous techno-optimism and techno-pessimism, and self-improvement stoicism,” according to Max Read, who writes on tech and Internet culture. In other words, a typical-enough diet for a contemporary twentysomething computer-science guy, and certainly not the stuff of alarm.

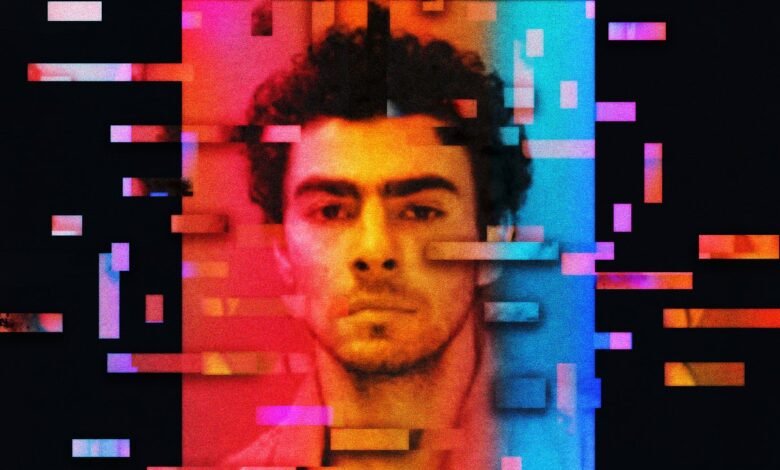

He is, by consensus, handsome, and jacked. “Holy happy trail, Batman!” Stephen Colbert enthused, over an en-plein-air portrait of a shirtless and beaming Luigi Mangione, who was briefly America’s most wanted man, and perhaps still is. “You know that guy’s Italian, because you could grate parmesan on those abs,” Colbert went on. (His fellow late-night host Taylor Tomlinson was more succinct: “Would.”) In his mug shot, Mangione, chiselled and defiant, appears ready for his closeup in a reboot of “Rocco and His Brothers.” He wears a hoodie well. On Monday night, a friend texted me a photograph of police escorting a dramatically backlit Mangione to his arraignment, and added, “Even the cops are trying to get him acquitted.”

Last week, Internet citizens were making dark, cathartic jokes about the fatal shooting, on December 4th, in Manhattan, of Brian Thompson, the chief executive officer of UnitedHealthcare, which is the insurance arm of the world’s largest health-care company. Now that Mangione has been provisionally identified as Thompson’s assailant, and has been arrested and charged with Thompson’s murder, the terminally online are decorating Mangione’s picture with glittery graphics and heart emojis, sharing fancams of Mangione scored to Charli XCX’s “Spring Breakers,” and editing Mangione into time-stamped snapshots to try and provide him with an alibi. (A sympathetic death-metal band posted to X, “Free Luigi who on December 4th around 6 AM helped us load our trailer and drive with us to play a secret set in California which is about 2.8k mi from Manhattan and at the show he bought merch from every band except for the hoodies because he said he hates them.”)

In trying to establish a motive for the alleged murder, authorities have cited a note that was apparently found on Mangione when he was arrested at a McDonald’s, in central Pennsylvania. “Frankly, these parasites simply had it coming,” it read. “A reminder: the US has the #1 most expensive healthcare system in the world, yet we rank roughly #42 in life expectancy.” The note also stated that UnitedHealthcare’s size and power have permitted it to “abuse our country for immense profit.” Thompson, who became C.E.O. in 2021, increased UnitedHealthcare’s profits by five billion dollars in just two years. Between 2019 and 2022, UnitedHealthcare more than doubled its denial rate for prior-authorization requests for post-acute care. One of Thompson’s signature innovations was to use a predictive algorithm to kick ailing and disabled Medicare patients out of nursing homes and rehabilitative programs, causing untold misery and penury. And UnitedHealthcare has increasingly demanded—and often denied—prior authorization for any number of ordinary necessities: colonoscopies, or insulin, or pain medication following major surgery, or physical, occupational, or speech therapy.

As of now, Mangione remains in Pennsylvania, where his legal team is fighting his extradition to New York. The support and affection for him that predominates online—its photo negative is the fear and loathing directed at our health-care system—appears to extend to the jail where he is being held. On Wednesday, Mangione’s fellow-inmates could be heard calling out of their windows, “Free Luigi!” and “Luigi’s conditions suck!” Meanwhile, Luigi merch is already hitting the market.

More than forty years ago, Richard E. Meyer, a scholar of American folklore, noted the essential difference between the outlaw—which Meyer defined as “a distinctively, though not exclusively, American folktype”—and the mere criminal. He wrote that “the American outlaw-hero is a ‘man of the people’; he is closely identified with the common people, and, as such, is generally seen to stand in opposition to certain established oppressive economic, civil and legal systems peculiar to the American historical experience.” (The italics are Meyer’s.) The outlaw-hero’s persona is that of a “good man gone bad,” not unlike the oncology patient Walter White, of “Breaking Bad,” who started cooking meth because his insurance didn’t cover his cancer treatments. To remain in good standing as an outlaw-hero, a man’s crimes must “be directed only toward those visible symbols which stand outside of and are thought of as oppressive toward the folk group,” Meyer writes. In exchange for both his audacity and his discretion, “the outlaw-hero is helped, supported and admired by his people.”

In the Reconstruction-era South, the outlaw-heroes Jesse James and Sam Bass “robbed banks and trains, symbols of the forces which kept the common man in economic and social bondage,” Meyer wrote. The bank robber and murderer Charles Arthur (Pretty Boy) Floyd, whose crimes spanned Ohio, Oklahoma, and Missouri during the Great Depression, idolized James as a Wild West spin on Robin Hood. Floyd took in possible tall tales “about how Jesse and his boys shared their bounty with widows and orphans,” Michael Wallis writes in “Pretty Boy: The Life and Times of Charles Arthur Floyd.” “Adoring fans said that when Jesse plundered a train, he examined the palms of the passengers and took valuables only from the ‘soft-handed ones.’ ”

Floyd likewise shared his loot with those in need; according to several accounts, Wallis writes, “when Charley robbed banks, he sometimes ripped up mortgages in shreds before the banker had an opportunity to get the papers recorded.” This magnanimous gesture, though it burnished Floyd’s legend, would have also considerably slowed his escape from the scene of his crime. He hid in plain sight: attending weddings and funerals, crashing with family and friends, and getting treated as a dreamboat celebrity wherever he went.

By contrast, Mangione lasted all of five days on the lam, and appears not to have redistributed any of UnitedHealthcare’s revenues. In other ways, though, he comfortably fits into Meyer’s taxonomy of the antihero. The U.S. health-insurance system is both “oppressive” and quintessentially “peculiar” to America, as the only developed nation in the world that does not provide universal health care. It has been widely speculated that Mangione’s alleged descent into violence may have been spurred by a debilitating back injury and subsequent spinal-fusion surgery. A health-care C.E.O. who receives ten million dollars in annual compensation is likely disqualified from membership in a “folk group,” and another note that Mangione reportedly wrote indicated that he did not want to endanger that group. (“What do you do? You wack the CEO at the annual parasitic bean-counter convention. It’s targeted, precise, and doesn’t risk innocents.”)

Like Floyd, Mangione may also have a knack for the myth-building flourish. Bullet casings left behind at the murder scene read “deny,” “defend,” and “depose,” borrowing from the obstructionist nomenclature of the health-insurance industry—as if its bureaucratic weapons were being turned against one of its own. And, although the manhunt for Mangione came to an ignominious end, early on, he hinted at being a more artful dodger, as when he allegedly left the perfect gag gift for the N.Y.P.D. in Central Park: a backpack stuffed with Monopoly money.

A fascinating artifact of the Mangione affair is the emergence, on TikTok and elsewhere, of the health-insurance murder ballad. (One of the most popular uses “deny, depose, defend” as a refrain.) This nascent subgenre flows directly from Woody Guthrie’s suite of murder ballads, which gave the workingman’s lament an infusion of antihero glamour. The subjects of Guthrie’s songs included Billy the Kid, Jesse James, and Charley Floyd, and it was in a song about Floyd that the bard of the Dust Bowl drew the brightest line between outlaw and oppressor: “Some will rob you with a six-gun / And some with a fountain pen / And as through your life you travel / Yes, as through your life you roam / You won’t never see an outlaw / Drive a family from their home.”

The standout among the neo-murder balladeers is the topical folk singer Jesse Welles, whose delivery and persona takes John Prine’s craggy empathy and adds a tincture of Brian Jones’s sinister charisma. His “United Health” dispenses with Thompson’s death in record time (“The ingredients you got bake the cake that you get”) and manages a potted history of the titular company inside a single verse (“Way back in seventy and seven / Mister Richard T. Burke started buyin’ H.M.O.s. . .”). It also neatly encapsulates the economic logic of for-profit insurance: “There’s an office in a building and a person in a chair / And you paid for it all though you may be unaware / You paid for the paper, you paid for the phone / You paid for everything they need to deny you what you’re owed.”

Much has been said and written in the last week-plus about the “coarsening” of American society, which is supposedly exemplified by the meme-ification of Mangione and his alleged crime. Speaking only for myself, if I have “coarsened” lately, I don’t think the evidence is in how I’ve laughed at the howlingly unprintable things that friends have texted me about Mangione’s thirst traps, but in how much solace I’ve taken in this new canon of earnest, literal-minded, on-the-nose protest songs.

In 1992, at a Bob Dylan tribute concert at Madison Square Garden, Eddie Vedder and Mike McCready, of Pearl Jam, performed Dylan’s “Masters of War.” The song isn’t a straight murder ballad but rather a murder-fantasy ballad, at once minimalist and maximalist. It’s mainly a D-minor chord strummed over and over—no chorus, no bridge, just verse after verse of the young Dylan, Guthrie’s artistic heir, finding more and yet more images and epithets to express just how much he despises and condemns the death merchants of the Cold War-era military-industrial complex. The song was then almost thirty years old, and in the first stages of a decades-long popular revival, sparked by Dylan’s own electrified and largely incomprehensible rendition of it at the 1991 Grammys. But it was new to me, and Vedder’s version was unnervingly lucid, unadorned, and matter-of-fact in its fury. Every word was clear:

The music critic Greil Marcus has written about how “Masters of War” is at once “bad art, a bad song”—“awful,” even—and an immortal classic, and how its greatness rests on what one might call its coarseness. The song is repetitive and relentless. It has one thing to say, and says it again; it keeps hitting the same note of hate, but harder. Die, death, death, dead. What appeals to listeners about “Masters of War,” according to Marcus, is “the way the song does go too far, to the limits of free speech.” Dylan, Marcus goes on, “gives people permission to go that far.”

Mangione allegedly took a human life, which is despicable. This act did not justify itself. But this act also gave people permission to go far enough—to acknowledge their righteous hatred of our depraved health-care system, and even to conjure something funny or silly or joyous out of that hate. The folk hero is a folk hero precisely because he does what we would never dare. Most of us have felt something like hate in our lives; most of us would never dream of harming anyone. Hatred corrodes the soul, but the smallest sip of it, now and then, can be intoxicating. It can remind us that we are still alive. ♦