Frustrated by lack of water quality data, citizen scientist Gary Francis monitors the Gowanus Canal himself

It looks like it’s raining in Gowanus. It could be — the sky is sunless and gray, and rings form on the surface of the Gowanus Canal every so often — but it isn’t.

The cause of the rings is methane gas, released by decomposing organic material, which lies on the bottom of the canal. Dead plants make up some of it, but mostly, it’s human feces, which ends up in the canal during rain storms when the combined sewer system can’t handle the increased water flow.

“That’s from the latest sewage that came out. Every time there’s a big combined sewer overflow event, there’s like a fresh layer of stuff,” said Gary Francis, Gowanus resident of nearly 15 years, pulling five probes out of the water. Since August last year, he has monitored the canal almost daily to shed light on the health of one of the nation’s most polluted bodies of water.

Since Feb. 28, the canal has seen six combined sewer overflow events, and the odor emanating from the water provides ample evidence. At the top of the waterway where Douglass Street ends, the smell of raw sewage mixes with that of coal tar leaking into the canal from one of the Brownfield sites that lie alongside it.

While Francis, a scientist only by hobby, has observed and cared for the canal for many years — a necessity for someone who uses it for paddle boarding and canoeing — it was a singular, catastrophic event that spurred him into action.

Sewer overflow tanks water quality in the Canal

The morning after a thunderstorm passed over the city on July 14, residents of Gowanus woke up to tens of thousands of dead fish — primarily Atlantic menhaden, a tiny filter feeder whose resurgence in New York harbors in recent years is an important reason for the return of whales and dolphins, but also other species — floating on the surface of the canal. The cause was a nearly complete lack of dissolved oxygen in the water, which asphyxiated both fish and other aquatic life.

At below 5 mg/L, oxygen levels were already considered stressful for aquatic life due to the warm weather and the temporary shut-off of the flushing tunnel, which has been turned off while the clean-up of the canal is ongoing. A combined sewer overflow event, brought upon by the thunderstorm, turned the water from stressful to deadly.

The sudden die-off of aquatic life reignited a rezoning conflict between the community and the city. With roughly 363 million gallons of combined sewer overflow discharge already being released into the canal yearly, the multiple buildings going up on both sides of the waterfront have raised concern over what effects approximately 20,000 new residents will have on the sewer system.

While much of this issue will be resolved once the two sewage overflow tanks currently under construction are finished, many will have moved into their new homes before both tanks stand ready in 2032.

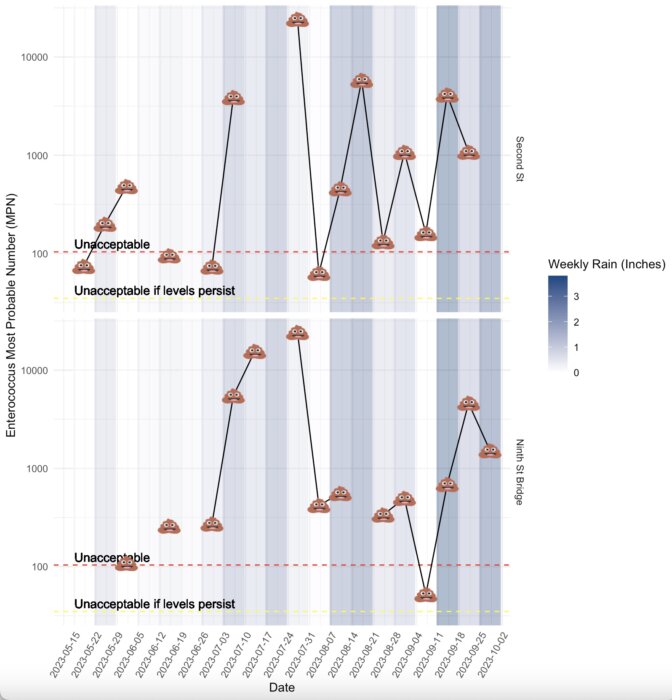

Yet, no reliable and sufficient data exist on what happens in the canal during a combined sewer overflow event. Anecdotally, it’s obvious — observations by passersby of feces, diapers, plastics, dead rats and whatever else Brooklyners flush down their toilets are frequent — but the Environmental Protection Agency only collects data twice a month; as does the New York City Department of Environmental Protection, and it stopped sharing its data with the public in 2022. (The EPA publishes its data on the Gowanus Superfund website.)

“By my awareness of the water and by spending time working on it, I knew what was in it. But I didn’t have any way to prove it. It was just me saying something,” Francis explained. “It set me off on a real mission just to get good data.”

Citizens become stewards of the Canal

Since the end of August, Francis has biked along the canal nearly every morning, stopping occasionally to drop his probes into the water.

Tracking the changes in water quality so minutely has allowed for trends to show that which would be impossible to notice with biweekly monitoring.

“The key is long-term monitoring,” said Brian Wilson, founder and CEO of Duro UAS, the company that built the device Francis uses.

Most people only conduct spot monitoring; the downside is that it only provides a snapshot of the water quality. Testing the water only every so often does not capture the natural cycles of the environment and their impact on it.

“It’s not telling you five minutes later or five minutes before,” Wilson said. “So, long-term monitoring is what’s going to allow you to see changes happening in the water.”

In late summer and fall, when temperatures were still high, it took until around the third day for dissolved oxygen to plummet to dangerous levels following a combined sewer overflow. As temperatures fell, however, average levels of dissolved oxygen rose, and it took longer to drop below 5 mg/L, around five days, Francis said.

But his data also showed that it’s often not as simple. Other factors are also at play.

“It’s so dynamic, it’s so complex. Water quality can change overnight — for the better — because of wind direction,” he explained. In the winter, prevailing winds blowing from the northwest push oxygenated water into the canal, leading to dissolved oxygen rebounding quicker than in the summer.

Case in point: When a winter storm passed over the city on the night of Jan. 10, Gowanus saw two inches of rainfall in only a few hours. Dissolved oxygen levels dove below 5 mg/L the day after due to the sewage water discharged into the canal. But a strong western wind in the days following quickly brought dissolved oxygen above 10 mg/L, unusual for the canal, even in the winter.

And therein lies a lesson about water stewardship that reaches beyond Gowanus, argued Francis.

“It’s crazy how quick nature can fix itself if we just give it a chance,” he said. Still, humans need to do their part, too.

“The canal is actually a really good example of how to do that. It’s a microcosm of some of the worst human mistakes that we’ve made, and it’s actually getting corrected in the best way that we can,” he noted.

People can argue about the best way of cleaning up the canal,” Francis said, “But the real bottom line is: It’s being corrected in a massive way that will support life.”

Francis isn’t the only steward of the Gowanus Canal. Several organizations and their members, like the Gowanus Canal Conservancy and the Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club—of which Francis is captain—also monitor the water and the uplands surrounding it and advocate for the community.

Eymund Diegel, a longtime member of the Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club, moved to Gowanus in the mid-90s, long before the gentrification of the neighborhood got going in earnest. Although he now lives in Sunset Park, Gowanus was Diegel’s home for 20 years; from his canoe, he saw the neighborhood evolve, and the canal with it.

He takes a pragmatic stance toward the new developments in the area. But it must be done sensibly, and that’s why Francis’ work — and that of other community stewards — is important, he explained.

“They’re putting out a lot of common sense ideas for what constitutes resilience,” Diegel said. By monitoring the water, what solutions work where can be studied. Sometimes, he noted, letting nature be the solution is better.

“We lose perspective with some of the basic environmental forces that keep the neighborhood healthy.”

Francis, a Briton born on a dairy farm in southwest England, has always held water and nature close. He was a competitive swimmer as a child and learned to surf during a trip to Australia. He moved to the United States when he was 21 as a part of a crew sent across the Atlantic to restore the New Jersey State House.

After a few years, Francis found himself in Maine, building wooden boats. There, he learned to sail, a skill that later would take him to the U.S. Virgin Islands, where he stayed for 16 years surfing, free diving and paddle boarding.

Career and a child brought him and his then-partner to Gowanus. When they parted ways, the canal became a way for Francis to heal.

“Getting back into the water was definitely part of my healing from a very bad breakup,” he said. “I’ve always found my way to the water when I’ve needed it.”

“I think he started paddling and being on the water as a way of taking care of his own mental health, getting out there and paddling and looking after himself,” said Celeste LeCompte, Francis’ partner since they met volunteering with the Dredgers Canoe Club a few years ago. She moved to Gowanus in 2016 and has become an active advocate for the community.

LeCompte has seen how Francis’ connection to the canal has evolved during their relationship.

“Over time, I think that opens you up to more observation and feeling more connected to the thing that you’re doing,” she said.

Francis has lived a life on and in the water, be it the rivers of Somerset, England, the Pacific or Atlantic Ocean, or the Gowanus Canal. Now, settled down in Gowanus for the long haul, he wants to share what he’s learned with the next generation.

“Now, I feel like I’m trying to repay some of this debt that I’ve incurred from the world, from nature, and help save it for my kids and the community. And that’s what makes me feel good now.”